Chapter 2. Recursion and lists

Recursion is a useful concept for both procedures and data. You may already be familiar with recursive procedures, but we'll review the concept in this chapter to make sure. Then we'll see that recursion is equally useful when talking about data: In particular, we'll look at one important category of recursive data, the linked list.

2.1. Recursive procedure

A recursive procedure is a procedure that sometimes calls itself to accomplish its task. One classical example of a recursive procedure is one for computing the nth Fibonacci number. The Fibonacci sequence starts as:

Each Fibonacci number fibn is the sum of the two preceding numbers, fibn − 1 + fibn − 2, starting with fib0 = 0 and fib1 = 1. We can easily translate this definition into a recursive method.

static int fibonacci(int n) {

if(n <= 1) return n;

else return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}

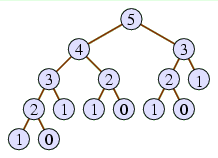

In talking about recursive procedures such as this, it's useful

to be able to diagram the various method calls performed. We'll

do this using a fibonacci(5) would be as follows.

Figure 2.1: Recursion tree for computing

fibonacci(5).

The recursion tree has the original parameter (5 in this case) at the

top, representing the original call to the method. In the case of

fibonacci(5), there would be two recursive calls,

to fibonacci(4) and

fibonacci(3), so we include 4 and 3 in our diagram

below 5 and draw a line connecting them.

Of course, fibonacci(4) has two recursive calls

itself, diagrammed in the recursion tree, as does

fibonacci(3). The complete diagram depicts all the

recursive calls to fibonacci made in the course of

computing fibonacci(5). The bottom of the recursion

tree depicts those cases when there are no recursive calls —

in this case, when n <= 1.

Note that every recursive procedure must have at least one

condition where there are no

recursive calls. Such a condition is called a

fibonacci method

has one base case, when n is less than or equal to 1.

Without a base case, the method will never terminate: It will

call itself infinitely.

With Java, this normally overflows memory, and the program ends

up terminating with a

StackOverflowException.

Though Fibonacci computation is a classical example of recursion, it has a major shortcoming: It's not a compelling example. There are two reasons for this. First, how often do you expect to want to compute Fibonacci numbers? (The Fibonacci sequence is admittedly useful occassionally for analyzing phenomena, but even those cases rarely require computing large Fibonacci numbers.) And second, the above recursive method isn't a good technique for doing it anyway. In fact, if you measure the speed by the number of additions performed, the recursive technique above will take fibn − 1 additions; to see this, you can take the above recursion tree and notice that the overall return value is computed as

Essentially, we are summing fibn 1's, which will require fibn − 1 additions. A much faster way is to start with the first two Fibonaccis and to extend the sequence one by one, each time adding the previous two numbers, until we reach the nth Fibonacci. Computing each Fibonacci requires just one addition, so the total number of additions is n − 1, which is much less than fibn − 1 for large n.

So let's look at a more compelling example: Suppose we want to

list all the subsets of elements in a list of strings named

elements. (Okay, I know what you're thinking:

Why would I ever want to list all the subsets of some set?

We wouldn't, but the same basic method works any time that we

want to search through all subsets. Suppose that we have a list

of valuables and their weights, and we want to choose those that fit

into a bag without overloading it. We can figure this out using a

program that goes through all subsets of the valuables. So, next time

that you rob a jewelry store, keep this method in mind.)

static void printSubsets(List<String> elements, List<String> current) {

if(elements.size() == 0) {

for(int i = 0; i < current.size(); i++) {

System.out.print(" " + current.get(i));

}

System.out.println();

} else {

String x = elements.remove(elements.size() - 1);

printSubsets(elements, current); // print subsets without x

current.add(x);

printSubsets(elements, current); // print subsets containing x

elements.add(x); // restore current and elements

current.remove(current.size() - 1); // to what they were

}

}

We can read this as follows: If elements is empty, we

simply display the elements of current.

But if it isn't empty, then we'll remove some element x from

elements, print all the subsets of elements

following its removal, then add x into current and

print all the subsets of elements again, but this time

with x printed out among the others. Finally, we restore

elements and current to where they were

previous to entering the recursive call, by adding x

back to elements and removing x from

current.

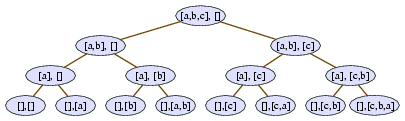

A recursion tree can help us to get a handle on how this works.

Suppose we called printSubsets with elements holding

three strings, a, b, and c.

Figure 2.2: Recursion tree for computing subsets of [a, b, c].

At the bottom is the case where elements is empty and

so current will be printed to System.out.

You can see that the current parameter

goes through all eight subsets of [a,b,c].

2.2. Recursive data

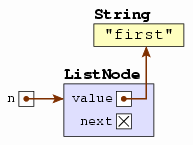

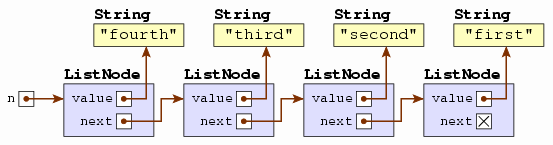

The concept of recursion applies also to data. In this context, we'll have a class that contains an object of the same class. The ListNode class of Figure 2.3 illustrates this.

Figure 2.3: The ListNode class.

1 class ListNode<E> {

2 private E value;

3 private ListNode<E> next;

4

5 public ListNode(E v, ListNode<E> n) { value = v; next = n; }

6

7 public E getValue() { return value; }

8 public ListNode<E> getNext() { return next; }

9

10 public void setValue(E v) { value = v; }

11 public void setNext(ListNode<E> n) { next = n; }

12 }

The recursive usage is in line 3:

Each ListNode instance will

have a ListNode variable named next within it.

Suppose we want to create a ListNode object. You may be temporarily stymied by the fact that in order to create a ListNode object, we must use the sole ListNode constructor (line 5), which requires a ListNode argument.

ListNode<String> n = new ListNode("first",???);

So what can we put in place of ????

As it happens, Java allows us to use null,

representing a non-object,

in places where objects are

required. We can use this here.

ListNode<String> n = new ListNode("first", null);

If we depict memory as it appears now, we'll see the following.

By the way, a program is not allowed to try to access a

null reference. Suppose we were to write the

following.

System.out.println(n.getNext().getValue());

Since

is a ListNode with a

n.getNext()getValue method, this will compile successfully.

But when the program is run, the computer will discover that

is in fact the non-object,

n.getNext()null, which doesn't have any methods.

In executing this statement, then, the system would terminate

the program, mentioning a

NullPointerException as the cause.

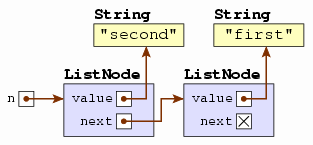

Consider how memory looks after then performing the following statement.

n = new ListNode<String>("second", n);

Now suppose we create two more nodes.

n = new ListNode<String>("fourth", new ListNode<String>("third", n));

You can see that what we get is something that looks

like a line, with each node remembering the node that comes

behind it in line. The "fourth" string comes first in

line, followed by "third", then "second", and

finally "first". We call such a linear structure a

More specifically, this is a

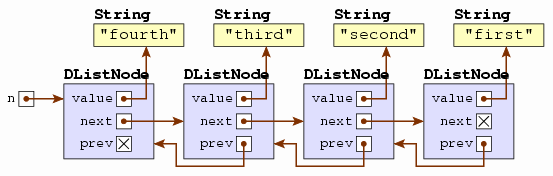

Figure 2.4 contains the DListNode class for

representing each node of a doubly linked list. The only changes are the

new prev instance variable, the addition

of a corresponding parameter in the constructor, and the

getPrevious and setPrevious methods.

Figure 2.4: The DListNode class.

1 class DListNode<E> {

2 private E value;

3 private DListNode<E> next;

4 private DListNode<E> prev;

5

6 public DListNode(E v, DListNode<E> n, DListNode<E> p) {

7 value = v; next = n; prev = p;

8 }

9

10 public E getValue() { return value; }

11 public DListNode<E> getNext() { return next; }

12 public DListNode<E> getPrevious() { return prev; }

13

14 public void setValue(E v) { value = v; }

15 public void setNext(DListNode<E> n) { next = n; }

16 public void setPrevious(DListNode<E> p) { prev = p; }

17 }

While a doubly linked list is marginally more complicated and takes a bit more memory than a singly linked list, it has the advantage that given a reference to a single node in the middle of the list, we can move both directions. Also, if we want to remove a node n from the middle of a list, we can extract it by simply modifying the next and previous nodes' references to n to instead skip over n.

n.getPrevious().setNext(n.getNext()); // update previous node's next

n.getNext().setPrevious(n.getPrevious()); // update next node's previous

In contrast, when we remove a node n from a singly linked list, we

must know where the preceding node is in order to change its

next pointer to skip over n, and that information is

not readily available from n alone. The only solution

is to remember the preceding node as we step along the

list to find n, which complicates the removal process

significantly.

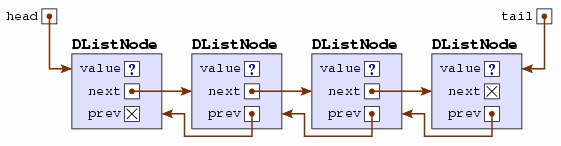

In a doubly linked list, we usually maintain references to both ends of the list, typically called the head and the tail.

With variables referring to both the head and the tail, we can then easily add and remove items at either end of the list.

2.2.1. The LinkedList class

The java.util package includes a LinkedList class implementing the List interface using a doubly linked list. Figure 2.5 contains an example illustrating how the fundamental List methods could be implemented.

Figure 2.5: The LinkedList class.

1 public class LinkedList<E> implements List<E> {

2 private DListNode<E> head;

3 private DListNode<E> tail;

4 private int curSize;

5

6 public LinkedList() {

7 head = null;

8 tail = null;

9 curSize = 0;

10 }

11

12 public int size() {

13 return curSize;

14 }

15

16 public boolean add(E value) {

17 DListNode<E> n = new DListNode<E>(value, null, tail);

18 if(tail == null) head = n; // list must have been empty, so head changes

19 else tail.setNext(n); // update tail to refer to n instead

20 tail = n;

21 curSize++;

22 return true;

23 }

24

25 public E get(int index) {

26 return getNode(index).getValue();

27 }

28

29 public E set(int index, E value) {

30 DListNode<E> n = getNode(index);

31 E old = n.getValue();

32 n.setValue(value);

33 return old;

34 }

35

36 public void add(int index, E value) {

37 if(index == curSize) {

38 add(value);

39 } else {

40 DListNode<E> next = getNode(index);

41 DListNode<E> prev = next.getPrevious();

42 DListNode<E> n = new DListNode<E>(value, next, prev);

43

44 // repair forward references, then backward references

45 if(prev == null) head = n;

46 else prev.setNext(n);

47

48 if(next == null) tail = n;

49 else next.setPrevious(n.getPrevious());

50

51 curSize++;

52 }

53 }

54

55 public E remove(int index) {

56 DListNode<E> n = getNode(index);

57

58 // repair forward references, then backward references

59 if(n == head) head = n.getNext();

60 else n.getPrevious().setNext(n.getNext());

61

62 if(n == tail) tail = n.getPrevious();

63 else n.getNext().setPrevious(n.getPrevious());

64

65 curSize--;

66 return n.getValue();

67 }

68

69 private DListNode<E> getNode(int index) {

70 if(curSize - index <= index) { // tail is closer

71 DListNode<E> n = tail; // so start from list's end

72 for(int curIndex = curSize - 1; curIndex != index; curIndex--) {

73 n = n.getPrevious();

74 }

75 return n;

76 } else { // head is closer

77 DListNode<E> n = head; // so start from list's beginning

78 for(int curIndex = 0; curIndex != index; curIndex++) {

79 n = n.getNext();

80 }

81 return n;

82 }

83 }

93 }

As you can see in lines 2

and 3, the LinkedList class

maintains

references to both the first and last nodes of the list. Note that

any methods based on accessing elements by index — namely

get, set, and remove — work by

calling the private getNode method in

lines 69

to 83,

which first determines whether the

requested node is closer to the head or the tail, and then,

starting there, it steps toward the requested node.

This stepping process for get and set

for a LinkedList

is generally much less efficient than for an ArrayList.

Accessing the list's first and last elements, though, is particularly efficient with a linked list, and as a result programmers use LinkedLists most often when they want to work with the list's head and tail. In recognition of this, java.util's LinkedList class includes a few methods specifically for accessing the head and tail, even though these are not required by the List interface.

public E getFirst() { return head.getValue(); }

public E getLast() { return tail.getValue(); }

public E removeFirst() { return remove(0); }

public E removeLast() { return remove(curSize - 1); }

public void addFirst(E value) { add(0, value); }

public void addLast(E value) { add(value); }

2.2.2. Iterators

Frequently when we work with a list, we want to step through all elements of the list in order. An example of this cropped up in our ArrayList example (Figure 1.5) of testing whether a number k is prime by iterating through known primes to see whether any divide into k.

for(int i = 0; true; i++) {

int p = primes.get(i).intValue();

// and so on

Wanting to step through all the elements of a list like this is

quite common.

But using the above code with a LinkedList is quite inefficient,

because LinkedList's get method will step through up to

half the list to find the requested index.

In this code excerpt, we call get multiple times, each

time simply fetching the index one beyond the previous one.

As a result, the above fragment would end up stepping through

the beginning of the list multiple times, which is a waste.

There is a much faster way to step through the elements of a linked list: We can keep a DListNode variable, which would initially refer to the list's head, and each iteration step can move to the next node of the list.

for(DListNode<Integer> n = primes.head; true; n = n.getNext()) {

int p = n.getValue().intValue();

// and so on

This is much more efficient than using get repeatedly,

because it looks at each node once only.

This approach, however, is impossible outside the LinkedList

class, because the head instance variable is private.

The java.util designers considered how best to resolve this.

One solution would be to make head a public

variable, but this would violate the object-oriented design

principle that a class's internal representation should never be visible

to outside classes.

A slightly better solution would be to have a

getFrontNode method, which returns head, but

such a solution would be specific to the LinkedList class, and

the designers wanted a solution that could work across all

possible List implementations.

The solution they settled on was to add a new method to the List interface specifically for iterating through the data of a list.

public Iterator<E> iterator();

This method involves a new type — the Iterator interface.

public interface Iterator<E> {

public boolean hasNext();

public E next();

}

The Iterator interface defines a way for a List implementation to create an object that uses the best technique for stepping through that List; programmers who use the class, though, need not understand what that technique is. The interface includes two methods.

boolean hasNext()Returns

trueif there are any elements remaining unvisited.E next()Returns the next element in the collection and advances to the element following. The subsequent call to

nextwill return this following element instead (and would itself advance to the element after that).

(They defined the same iterator method for the Set

interface, too. There, the method is even more important, because

there is no get method; iterator is the primary

technique for accessing objects in the set.)

Thus, we could write our

prime-testing loop using the iterator method instead.

for(Iterator<Integer> it = primes.iterator(); true; ) {

int p = it.next().intValue();

// and so on

With the code written this way, it will be efficient whether

primes is an ArrayList or a LinkedList.

Often it happens that we have a list from which want to remove all elements meeting a particular condition — for example, we may have a list of students, from which we want to remove all who have a GPA below 1.0. The Iterator interface includes a third method for facilitating this.

void remove()Removes the element most recently returned by

nextfrom the Iterator's underlying collection.

As an example of this, consider the following code fragment

for removing words starting with a capital T from a list of

Strings. (An astute reader would notice a bug here:

If the list contains an empty string (""), then the

substring method would raise an exception for that

element.)

for(Iterator<String> it = list.iterator(); it.hasNext(); ) {

String cur = it.next();

if(cur.substring(0, 1).equals("T")) it.remove();

}

There is a complexity involved in the definition of the

Iterator interface that is worth mentioning: What

happens if a program modifies the underlying list in the middle

of iterating through it? For example, you

might imagine an algorithm that steps through a list and, when

it observes a particular condition, it adds new elements onto

the end. Should the Iterator step through these new elements

when it gets to them (because they are in the list at this

point) or not (because they weren't in the list at the time the

Iterator was created)? The java.util designers felt that if they went

with either choice, programmers would sometimes expect the opposite

behavior, and such bugs would be difficult to identify.

So the designers decided it was best to prohibit such programs

altogether: In particular,

they specify that if your program creates an Iterator for a list,

then changes the underlying list (without using the Iterator's

remove method), and then tries to use the

Iterator again, the Iterator should raise an exception —

a ConcurrentModificationException.

Should you see this exception, the

solution is to modify the program so that it doesn't

change the same list that it is currently attempting to iterate

through. Frequently, this is a matter of creating another list

holding all of the items to add, and then adding them after the

iteration through objects is complete.

Figure 2.6: Two implementations of the Iterator interface.

class LinkedIterator<E>

implements Iterator<E> {

private DListNode<E> next;

public LinkedIterator(DListNode<E> n) {

next = n;

}

public boolean hasNext() {

return next != null;

}

public E next() {

E ret = next.getValue();

next = next.getNext();

return ret;

}

}

class ArrayIterator<E> implements Iterator<E> {

private ArrayList<E> list;

private int nextIndex;

public ArrayIterator(ArrayList<E> l) {

list = l;

nextIndex = 0;

}

public boolean hasNext() {

return nextIndex < list.size();

}

public E next() {

E ret = list.get(nextIndex);

nextIndex++;

return ret;

}

}

Of course, to support the iterator method,

the ArrayList and LinkedList classes must have such methods,

and for this there would need to be classes that implement the

Iterator interface.

Figure 2.6 contains code illustrating

how the java.util package might define Iterator classes for both

LinkedList and ArrayList.

(These are simplified implementations:

They lack the required remove method, and

they need to provide support for throwing a

ConcurrentModificationException when the underlying list is

modified. We omit this part of the implementations, because the

hassle isn't too edifying.)

Notice that these classes are not visible outside the

java.util package where they are defined, for the first line does not

specify the classes as being public.

Instead, your program can call the

iterator method on a List implementation, and that

method will generate an instance of the relevant class for you.

For example,

LinkedList's iterator method might be as follows.

public Iterator<E> iterator() { return new LinkedIterator<E>(head); }

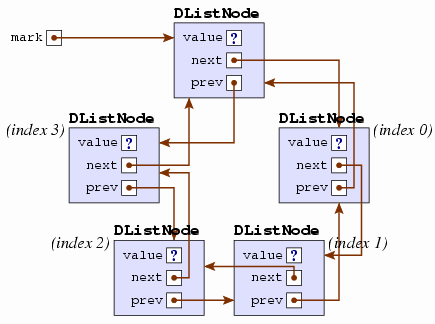

2.2.3. Circular lists

Some clever programmers have noticed that the implementation of a linked list can be shortened by introducing a new node (which we'll call the marker) and placing this node both before the head and after the tail. We end up with a structure like the following.

You can trace the next arrows around the nodes in a

circle, and for that reason this structure is called a

Figure 2.7: A circular LinkedList implementation

public class LinkedList<E> implements List<E> {

private DListNode<E> mark;

private int curSize;

public LinkedList() {

mark = new DListNode<E>(null, null, null);

mark.setNext(mark);

mark.setPrevious(mark);

curSize = 0;

}

public int size() {

return curSize;

}

public boolean add(E value) {

DListNode<E> n = new DListNode<E>(value, mark, mark.getPrevious());

mark.getPrevious().setNext(n);

mark.setPrevious(n);

curSize++;

return true;

}

public void add(int index, E value) {

DListNode<E> next = getNode(index);

DListNode<E> prev = next.getPrevious();

DListNode<E> n = new DListNode<E>(value, next, prev);

next.setPrevious(n);

prev.setNext(n);

curSize++;

}

public E remove(int index) {

DListNode<E> n = getNode(index);

n.getPrevious().setNext(n.getNext());

n.getNext().setPrevious(n.getPrevious());

curSize--;

return n.getValue();

}

private DListNode<E> getNode(int index) {

DListNode<E> n = mark;

if(curSize - index <= index) { // closer if we go backwards

for(int i = curSize; i != index; i--) n = n.getPrevious();

} else { // closer if we go forwards

for(int i = -1; i != index; i++) n = n.getNext();

}

return n;

}

// `get', `set', and `iterator' methods omitted

}

We can implement LinkedList using this concept instead, and

Figure 2.7 contains such an implementation

of most of List's interesting methods.

You can see that it is indeed shorter, particularly the second

add method and the remove method.

Whether this implementation is better is a debatable

point. As a rule of thumb, a shorter program —

particular one with fewer if statements, such as this

one — is more desirable, since there's less room for errors.

But there is also such a thing as being too clever,

and a programmer shouldn't make code more confusing just to save

keystrokes.

My own opinion is that this specific idea of a circular linked

list is on the borderline between being an elegant improvement

and being too clever for its own good.

2.2.4. Comparing with ArrayList

The java.util package defines two general-purpose List implementations, ArrayList and LinkedList. You're bound to wonder: So which is better?

The answer is that it depends. After all, if one were always better than the other, then the java.util designers wouldn't have bothered with including the worse alternative.

To see which is better, we can compare them method by method.

Getting the list's size (via

size) is equally fast for both. Though it's not as obvious, iterating through the elements with an Iterator is roughly equally efficient for both.For accessing specific elements via the

getandsetmethods, ArrayList is certainly better, since it can go directly to the element requested, whereas LinkedList must step to them starting from an end of the list.Using

addorremovenear the beginning of a list is much better for the LinkedList: An ArrayList must spend lots of time shifting all the elements to adapt to the change.Using

addorremovenear the end of a list is roughly the same. It's true that adding onto the end of an ArrayList sometimes takes a very long time (because it triggers the array doubling), but on average it takes a fixed amount of time no matter the list's size.Using

addorremovenear the middle of a list is bad for both but not clearly worse for one than the other.

Thus, if you have an algorithm that needs to use the

get and set methods heavily, use an ArrayList.

If you have an algorithm that frequently adds or removes elements

at the beginning of the list, use a LinkedList.

(Incidentally, if your algorithm

frequently adds or removes elements at the beginning of the

list, consider first whether it would help to keep the list in reverse

order so that the additions and removals would occur at the end

instead.)

And what if your algorithm doesn't do either one (like our prime-counting program)? There isn't much of a speed difference, so we might as well break the tie based on memory usage. Suppose we want n elements in our list. A LinkedList will create a new node for each value, each holding three references (one to refer to the value, two to refer to the next and previous nodes), for a total of 3 n references. (There is some additional overhead with every object allocation, involving at least one additional reference, so in fact the total memory allocated for the linked list will be at least 4 n. This overhead is not important to our point here, though.) In contrast, an ArrayList will create only one reference per array element — but because the array doubles in length each time it overflows, it may have as many as 2 n array elements. Thus, ArrayList uses less memory and so is the better choice.

The bottom line, then, is this: Use an ArrayList unless your program frequently adds or removes elements at the beginning of the list.