Chapter 19. Arrays

Often programs must manipulate many similar objects. For example, if

we were writing a program for searching the library's catalog, we might

imagine that the program would have a different object for each book.

We could hope to have a separate variable referencing each object, but

this isn't practical if our program deals with thousands of objects (as

with our library example). Luckily, Java provides a construct called an

array for this situation.

19.1. Basics

An array is essentially a line of variables

Each single variable in the array is called an

array element.

To create a variable for referencing an array, use a variable

declaration of the following form.

<typeOfElement>[] <arrayVariableName>;

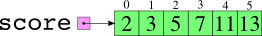

For example, the following creates a variable score

that can reference an array of numbers.

double[] score;

This creates a variable that can reference an array. Like object

variables, it does not actually reference an array yet.

To create an array and assign the array variable to reference it, we

will use the new keyword.

score = new double[6];

This is the syntax for creating an array: the new keyword,

followed by the type name of each array element, followed by the length

of the array enclosed in brackets. The integer in brackets can be any

expression (2 * numStudents

instead of 3

,

for example).

Creating such an array sets up the score variable to look as

follows in the computer's memory. (The numbers in the array, however,

all default to 0.)

To work with an array, we reference individual elements according to

their array index.

The first array element has an index of 0,

the second has an index of 1, and so on.

Yes, that's one less than the array length.

So if you declare an array score of length 3,

the three array indices are 0, 1, and 2, since Java always begins

numbering from 0.

(Starting from 0 turns out to be more convenient than the intuitive

choice of 1.)

So even though the array has a length of 3, there is no array element

with an index of 3

If you try to access an undefined array index,

the program will crash with an

ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException.

So be careful with array indices.

To refer to an array element in an expression, type the

array variable name, followed by the element's array index enclosed in

brackets. You can also do this on the

left-hand side of an assignment statement

to alter an array element's contents.

double[] score = new double[3];

score[0] = 97.0;

score[1] = 83.0;

score[2] = 66.0;

println("Average = " + ((score[0] + score[1] + score[2]) / 3.0));

In these statements we create an array of three numbers,

called score. We assigned its three boxes to refer to three

test scores, 97, 83, and 66. And finally we printed the

average of these. The computer will display 82.0.

The significance of arrays comes when you use an expression to

access a particular element of the array.

Figure 19.1

contains a short program that reads a

sequence of numbers into an array and then prints the numbers in

reverse order. For example, the user might experience the following in

running the program. (What the user types is in boldface.)

How many scores? 3

Type the scores now.

2

3

5

Here they are in reverse order.

5.0

3.0

2.0

There's no way we could write a program to accomplish this using what

we had seen in previous chapters. Using arrays, however, allows us to

store an arbitrarily large sequence of data with no troubles.

Figure 19.1: The PrintReverse program.

1 import acm.program.*;

2

3 public class PrintReverse extends Program {

4 public void run() {

5 // create the array

6 int num_scores = readInt("How many scores? ");

7 double[] score;

8 score = new double[num_scores];

9

10 // fill the array

11 for(int i = 0; i < num_scores; i++) {

12 score[i] = readDouble("Score " + i + ": ");

13 }

14

15 // print it in reverse

16 println("Here they are in reverse order.");

17 for(int i = num_scores - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

18 println(" " + score[i]);

19 }

20 }

21 }

Java includes a special technique for accessing the length of an

array, using the word length. In any expression, you can

write the array name, followed by a period and the word length,

and the value will be the number of items that the array was created to

hold.

As an example, we could rewrite

line 11 of

Figure 19.1 as follows.

for(int i = 0; i < score.length; i++) { //@ num_scores

It's preferable to use the length keyword when

appropriate, in favor of using some other variable that happens to

represent the length of the array.

You'll recall that the String class provides a length

method that returns the number of characters in a string. Thus, if we

want to know how long the String referenced by a variable

name is, we use name.length()

.

With arrays, though, length is a special word

built into Java, not a method. As a result, parentheses are not

applied to length when used with an array.

To determine how long the array

referenced by score, we type score.length

,

not score.length()

.

19.2. Computing the mode

We'll now consider a more complex problem. Suppose we have an array

of test scores, all integers between 0 and 100, and we want

to find the mode — that is, the integer occurring most

often. We'll see two techniques for computing this.

In the more obvious technique, found in

Figure 19.2, we'll go through each number in the

array and count how many times that number appears in the array.

As we go along, we track which number has appeared most often.

Once we complete counting each number in the array, we'll have found the

mode.

Figure 19.2: The computeMode method.

public int computeMode(int[] nums) {

int maxValue = -1;

int maxCount = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < nums.length; i++) {

// count number of times nums[i] is in array

int count = 0;

for(int j = 0; j < nums.length; j++) {

if(nums[j] == nums[i]) {

count++;

}

}

// remember the highest count we have seen

if(count > maxCount) {

maxValue = nums[i];

maxCount = count;

}

}

return maxValue;

}

An alternative technique is to create a second array, which I'll call

tally, which initially has 0 throughout. We then go through the

array of test scores, and with each score k, we increment

entry k of tally. By the end of this process,

tally[i] will hold the number of times i appears among the

test scores. Our last step is to see which entry in tally is

largest; the index of this entry is the mode.

Figure 19.3: The tallyMode method.

public int tallyMode(int[] nums) {

// create array of tallies, all initialized to zero

int[] tally = new int[101];

for(int i = 0; i < tally.length; i++) {

tally[i] = 0;

}

// for each array entry, increment corresponding tally box

for(int i = 0; i < nums.length; i++) {

int value = nums[i];

tally[value]++;

}

// now find the index of the largest tally - this is the mode

int maxIndex = 0;

for(int i = 1; i < tally.length; i++) {

if(tally[i] > tally[maxIndex]) {

maxIndex = i;

}

}

return maxIndex;

}

This second technique can often be significantly faster: It looks at

each test score only once, whereas the first technique will look at each

test score as many times as there are test scores. That is, if our

parameter array contains n test scores, the first technique

will look into the array n² times, whereas the second

technique will look into the array only n times.

19.3. Arrays of objects

So far we have been working with arrays of numbers. But we can have

arrays of any type of thing we want. For example, suppose we want to

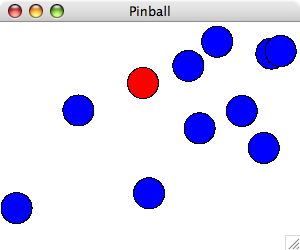

simulate a ball bouncing around a window with several circular bumpers

inside it.

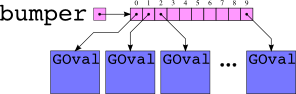

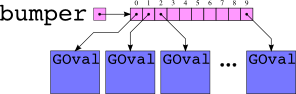

We might want to store the bumpers as an array of

GOvals. Creating such an array is easy enough.

GOval[] bumper = new GOval[10];

However, this doesn't itself create an array of 10 GOval

objects: It creates 10 GOval variables, which can potentially

reference GOval boxes. But these array entries default to

null, and it is our job to populate the array with references

to GOval objects.

for(int i = 0; i < bumper.length; i++) {

double x = Math.random() * (getWidth() - 30);

double y = Math.random() * (getHeight() - 30);

bumper[i] = new GOval(x, y, 30, 30);

bumper[i].setFilled(true);

bumper[i].setFillColor(new Color(0, 0, 255));

this.add(bumper[i]);

}

The following diagram illustrates what will be in memory after the

array has been populated.

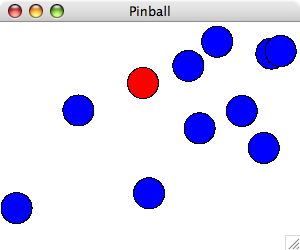

Figure 19.4 contains a complete program implementing

a ball bouncing off of circular bumpers. The logic involved uses a tad

of trigonometry. This isn't the point of this chapter, so I'll

conveniently avoid explaining it here.

Figure 19.4: The Pinball program.

import acm.program.*;

import acm.graphics.*;

import java.awt.*;

public class Pinball extends GraphicsProgram {

public void run() {

// Create the ball that will bounce around the screen

GOval ball = new GOval(25, 25, 30, 30);

ball.setFilled(true);

ball.setFillColor(new Color(255, 0, 0));

this.add(ball);

// Create the bumpers off of which the ball will bounce

GOval[] bumper = new GOval[10];

for(int i = 0; i < bumper.length; i++) {

double x = Math.random() * (getWidth() - 30);

double y = Math.random() * (getHeight() - 30);

bumper[i] = new GOval(x, y, 30, 30);

bumper[i].setFilled(true);

bumper[i].setFillColor(new Color(0, 0, 255));

this.add(bumper[i]);

}

double theta = Math.PI / 6; // ball's current direction

while(true) {

// wait for one frame, step ball once in current direction

this.pause(20);

ball.move(3 * Math.cos(theta), 3 * Math.sin(theta));

// update direction if bounce off window's edge or bumper

double x = ball.getX();

double y = ball.getY();

if(x < 0 || x + 30 >= this.getWidth()) {

theta = Math.PI - theta; // hits window's left/right edge

} else if(y < 0 || y + 30 >= this.getHeight()) {

theta = -theta; // hits window's top/bottom edge

} else {

for(int i = 0; i < bumper.length; i++) {

double dx = bumper[i].getX() - x;

double dy = bumper[i].getY() - y;

if(dx * dx + dy * dy < 30 * 30) { // hits bumper

double in = Math.atan2(dy, dx);

theta = (in + Math.PI) - (theta - in);

}

}

}

}

}

}